The film itself is an almost dizzying exercise in Star Wars meta-nostalgia, down to the villain Kylo Ren’s fanboying over his grandfather Darth Vader. The layered richness of Williams’s work is perhaps best showcased in 2014’s Episode VII: The Force Awakens. It’s this use of music as an active vehicle for storytelling that has made it as much a part of the films’ internal mythology as ancient Sith Lords and Jedi temples.

“Anakin’s Theme” from Episode I: The Phantom Menace is studded with soft references to “The Imperial March” (Vader’s theme) it’s a musical foreshadowing of Vader’s rise that’s in some ways more effective than the visual cues of the film itself, which wasn’t very good. Listening to Star Wars soundtracks, which are as cherished as the films themselves in my home, it’s possible to reconstruct precise plot details I often recall events simply by whistling their themes. In that way, the franchise has more in common with Wagnerian epic opera than with your standard action movie, where sound is so often used to trigger a quick emotion. Luke’s father Darth Vader and the Empire he represents, on the other hand, are driven by timpani, staccato strings, and boisterous brass, in a theme that has become so associated with power that sports antiheroes and would-be villains use it.Ī big part of what makes Williams’s music so resonant is his consistent, masterful use of shifting themes-across all of the films-to carry ideas and represent characters. The leitmotif has come to symbolize Luke and the Force, and is arguably one of the most recognizable seven-note sequences in American music. Williams’s composing hand and the London Symphony Orchestra’s strings, for instance, turn a wordless moment in the original Star Wars film into a profound contemplation of power and self-realization. What’s a Star Wars film without John Williams? It’s a hard question to answer when you consider the careful, virtuoso work he’s done to flesh out and develop a universe of figures and knotted allegiances.

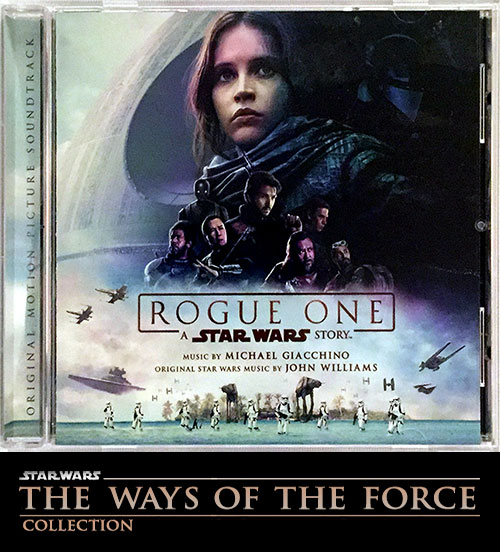

Netflix’s Inventing Anna Writes a Check It Can’t Cash Shirley Li So when I found out that Rogue One: A Star Wars Story would be the franchise’s first live-action film without Williams at its center, I was apprehensive. Williams’s music has been as vital to my love of Star Wars as have light sabers and giant weapons with rather conspicuous weaknesses. But for me, perhaps the most singular contribution has come from the legendary composer John Williams, of Jaws, Indiana Jones, and Jurassic Park fame. Of course, there are the actors themselves, and the legions of mimics in science fiction and fantasy. In the 39 years the franchise has been in existence, creator George Lucas has had a lot of help in its success and integration into popular culture.

The villains of my youth were imitating shadows of the Dark Side, clad in capes and cybernetics, and the heroes were paler imitations of the didactic duos of Obi-Wan and Luke. There were numerous video games, toys, comics, spin-offs, and an entire new trilogy of films by my twelfth birthday, and characters like Darth Vader, Luke Skywalker, and Han Solo had long been cultural icons. Star Wars was already deeply embedded in American pop culture by the time I was a kid.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)